Redistricting in North Carolina

Redistricting is the process by which new congressional and state legislative district boundaries are drawn. Each of North Carolina's 13 United States representatives and 170 state legislators are elected from political divisions called districts. United States senators are not elected by districts, but by the states at large. District lines are redrawn every 10 years following completion of the United States census. The federal government stipulates that districts must have nearly equal populations and must not discriminate on the basis of race or ethnicity.[1][2][3][4]

North Carolina was apportioned 14 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives after the 2020 census, 1 more than it received after the 2010 census.

On October 25, 2023, the North Carolina General Assembly adopted new congressional district boundaries.[5] The legislation adopting the new maps passed the State Senate by a vote of 28-18 and the State House by a vote of 64-40.[6] Both votes were strictly along party lines with all votes in favor by Republicans and all votes against by Democrats.[7][8]

The New York Times' Maggie Astor wrote, "The map creates 10 solidly Republican districts, three solidly Democratic districts and one competitive district. Currently, under the lines drawn by a court for the 2022 election, each party holds seven seats. The Democratic incumbents who have been essentially drawn off the map are Representatives Jeff Jackson in the Charlotte area, Kathy Manning in the Greensboro area and Wiley Nickel in the Raleigh area. A seat held by a fourth Democrat, Representative Don Davis, is expected to be competitive."[5]

On April 28, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court overturned their February 4, 2022, decision that the state's enacted congressional and legislative maps were unconstitutional due to partisan gerrymandering and vacated both the maps the legislature enacted in 2021 and the remedial maps used for the 2022 elections.[9] In its ruling, the court said, "we hold that partisan gerrymandering claims present a political question that is nonjusticiable under the North Carolina Constitution. Accordingly, the decision of this Court in Harper I is overruled. We affirm the three judge panel’s 11 January 2022 Judgment concluding, inter alia, that partisan gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable, political questions and dismissing all of plaintiffs’ claims with prejudice."Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many On October 25, 2023, the North Carolina General Assembly adopted new legislative district boundaries.[10] The legislation adopting the new Senate districts passed the State Senate by a vote of 28-17 and the State House by a vote of 63-40.[11] The legislation adopting the new House districts passed the State Senate by a vote of 27-17 and the State House by a vote of 62-44.[12] All four votes were strictly along party lines with all votes in favor by Republicans and all votes against by Democrats.[13][14][15][16] WUNC's Rusty Jacobs wrote that Catawba College Prof. Michael "Bitzer said Republicans have drawn maps that have a strong chance of preserving their veto-proof super majorities in both chambers of the state legislature. Bitzer noted that constitutional provisions, like requiring legislators to keep counties whole when drawing state legislative districts, make it more difficult for lawmakers to gerrymander these maps more aggressively."[17]

The Carolina Journal's Alex Baltzegar reported that "The John Locke Foundation recently released its annual Civitas Partisan Index scores for the legislative maps, which found there to be 28 Republican-leaning seats, 17 Democrat-leaning seats, and five toss-ups in the state Senate map."[10] Baltzegar also reported that "The new state House map would yield approximately 69 Republican and 48 Democratic seats, with three being in the swing category, according to Civitas’ CPI ratings. However, state House districts are smaller, and political outcomes vary to a higher degree. Many of the “lean” Republican or Democrat seats could be won by either party, and political shifts and trends will influence certain districts in the future."[10]

On April 28, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court overturned their February 4, 2022, decision that the state's enacted congressional and legislative maps were unconstitutional due to partisan gerrymandering and vacated both the maps the legislature enacted in 2021 and the remedial maps used for the 2022 elections.[18] In its ruling, the court said, "we hold that partisan gerrymandering claims present a political question that is nonjusticiable under the North Carolina Constitution. Accordingly, the decision of this Court in Harper I is overruled. We affirm the three judge panel’s 11 January 2022 Judgment concluding, inter alia, that partisan gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable, political questions and dismissing all of plaintiffs’ claims with prejudice."Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many Click here for more information on maps enacted after the 2020 census.

See the sections below for further information on the following topics:

- Background: A summary of federal requirements for redistricting at both the congressional and state legislative levels

- State process: An overview about the redistricting process in North Carolina

- District maps: Information about the current district maps in North Carolina

- Redistricting by cycle: A breakdown of the most significant events in North Carolina's redistricting after recent censuses

- State legislation and ballot measures: State legislation and state and local ballot measures relevant to redistricting policy

- Political impacts of redistricting: An analysis of the political issues associated with redistricting

Background

This section includes background information on federal requirements for congressional redistricting, state legislative redistricting, state-based requirements, redistricting methods used in the 50 states, gerrymandering, and recent court decisions.

Federal requirements for congressional redistricting

According to Article I, Section 4 of the United States Constitution, the states and their legislatures have primary authority in determining the "times, places, and manner" of congressional elections. Congress may also pass laws regulating congressional elections.[19][20]

| “ | The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.[21] | ” |

| —United States Constitution | ||

Article I, Section 2 of the United States Constitution stipulates that congressional representatives be apportioned to the states on the basis of population. There are 435 seats in the United States House of Representatives. Each state is allotted a portion of these seats based on the size of its population relative to the other states. Consequently, a state may gain seats in the House if its population grows or lose seats if its population decreases, relative to populations in other states. In 1964, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Wesberry v. Sanders that the populations of House districts must be equal "as nearly as practicable."[22][23][24]

The equal population requirement for congressional districts is strict. According to All About Redistricting, "Any district with more or fewer people than the average (also known as the 'ideal' population), must be specifically justified by a consistent state policy. And even consistent policies that cause a 1 percent spread from largest to smallest district will likely be unconstitutional."[24]

Federal requirements for state legislative redistricting

The United States Constitution is silent on the issue of state legislative redistricting. In the mid-1960s, the United States Supreme Court issued a series of rulings in an effort to clarify standards for state legislative redistricting. In Reynolds v. Sims, the court ruled that "the Equal Protection Clause [of the United States Constitution] demands no less than substantially equal state legislative representation for all citizens, of all places as well as of all races." According to All About Redistricting, "it has become accepted that a [redistricting] plan will be constitutionally suspect if the largest and smallest districts [within a state or jurisdiction] are more than 10 percent apart."[24]

State-based requirements

In addition to the federal criteria noted above, individual states may impose additional requirements on redistricting. Common state-level redistricting criteria are listed below.

- Contiguity refers to the principle that all areas within a district should be physically adjacent. A total of 49 states require that districts of at least one state legislative chamber be contiguous (Nevada has no such requirement, imposing no requirements on redistricting beyond those enforced at the federal level). A total of 23 states require that congressional districts meet contiguity requirements.[24][25]

- Compactness refers to the general principle that the constituents within a district should live as near to one another as practicable. A total of 37 states impose compactness requirements on state legislative districts; 18 states impose similar requirements for congressional districts.[24][25]

- A community of interest is defined by FairVote as a "group of people in a geographical area, such as a specific region or neighborhood, who have common political, social or economic interests." A total of 24 states require that the maintenance of communities of interest be considered in the drawing of state legislative districts. A total of 13 states impose similar requirements for congressional districts.[24][25]

- A total of 42 states require that state legislative district lines be drawn to account for political boundaries (e.g., the limits of counties, cities, and towns). A total of 19 states require that similar considerations be made in the drawing of congressional districts.[24][25]

Methods

In general, a state's redistricting authority can be classified as one of the following:[26]

- Legislature-dominant: In a legislature-dominant state, the legislature retains the ultimate authority to draft and enact district maps. Maps enacted by the legislature may or may not be subject to gubernatorial veto. Advisory commissions may also be involved in the redistricting process, although the legislature is not bound to adopt an advisory commission's recommendations.

- Commission: In a commission state, an extra-legislative commission retains the ultimate authority to draft and enact district maps. A non-politician commission is one whose members cannot hold elective office. A politician commission is one whose members can hold elective office.

- Hybrid: In a hybrid state, the legislature shares redistricting authority with a commission.

Gerrymandering

- See also: Gerrymandering

The term gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district lines to favor one political party, individual, or constituency over another. When used in a rhetorical manner by opponents of a particular district map, the term has a negative connotation but does not necessarily address the legality of a challenged map. The term can also be used in legal documents; in this context, the term describes redistricting practices that violate federal or state laws.[1][27]

For additional background information about gerrymandering, click "[Show more]" below.

The phrase racial gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district lines to dilute the voting power of racial minority groups. Federal law prohibits racial gerrymandering and establishes that, to combat this practice and to ensure compliance with the Voting Rights Act, states and jurisdictions can create majority-minority electoral districts. A majority-minority district is one in which a racial group or groups comprise a majority of the district's populations. Racial gerrymandering and majority-minority districts are discussed in greater detail in this article.[28]

The phrase partisan gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district maps with the intention of favoring one political party over another. In contrast with racial gerrymandering, on which the Supreme Court of the United States has issued rulings in the past affirming that such practices violate federal law, the high court had not, as of November 2017, issued a ruling establishing clear precedent on the question of partisan gerrymandering. Although the court has granted in past cases that partisan gerrymandering can violate the United States Constitution, it has never adopted a standard for identifying or measuring partisan gerrymanders. Partisan gerrymandering is described in greater detail in this article.[29][30]Recent court decisions

The Supreme Court of the United States has, in recent years, issued several decisions dealing with redistricting policy, including rulings relating to the consideration of race in drawing district maps, the use of total population tallies in apportionment, and the constitutionality of independent redistricting commissions. The rulings in these cases, which originated in a variety of states, impact redistricting processes across the nation.

For additional background information about these cases, click "[Show more]" below.

Gill v. Whitford (2018)

- See also: Gill v. Whitford

In Gill v. Whitford, decided on June 18, 2018, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the plaintiffs—12 Wisconsin Democrats who alleged that Wisconsin's state legislative district plan had been subject to an unconstitutional gerrymander in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments—had failed to demonstrate standing under Article III of the United States Constitution to bring a complaint. The court's opinion, penned by Chief Justice John Roberts, did not address the broader question of whether partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable and remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings. Roberts was joined in the majority opinion by Associate Justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. Kagan penned a concurring opinion joined by Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor. Associate Justice Clarence Thomas penned an opinion that concurred in part with the majority opinion and in the judgment, joined by Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch.[31]

Cooper v. Harris (2017)

- See also: Cooper v. Harris

In Cooper v. Harris, decided on May 22, 2017, the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed the judgment of the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina, finding that two of North Carolina's congressional districts, the boundaries of which had been set following the 2010 United States Census, had been subject to an illegal racial gerrymander in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Justice Elena Kagan delivered the court's majority opinion, which was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor (Thomas also filed a separate concurring opinion). In the court's majority opinion, Kagan described the two-part analysis utilized by the high court when plaintiffs allege racial gerrymandering as follows: "First, the plaintiff must prove that 'race was the predominant factor motivating the legislature's decision to place a significant number of voters within or without a particular district.' ... Second, if racial considerations predominated over others, the design of the district must withstand strict scrutiny. The burden shifts to the State to prove that its race-based sorting of voters serves a 'compelling interest' and is 'narrowly tailored' to that end." In regard to the first part of the aforementioned analysis, Kagan went on to note that "a plaintiff succeeds at this stage even if the evidence reveals that a legislature elevated race to the predominant criterion in order to advance other goals, including political ones." Justice Samuel Alito delivered an opinion that concurred in part and dissented in part with the majority opinion. This opinion was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy.[32][33][34]

Evenwel v. Abbott (2016)

- See also: Evenwel v. Abbott

Evenwel v. Abbott was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2016. At issue was the constitutionality of state legislative districts in Texas. The plaintiffs, Sue Evenwel and Edward Pfenninger, argued that district populations ought to take into account only the number of registered or eligible voters residing within those districts as opposed to total population counts, which are generally used for redistricting purposes. Total population tallies include non-voting residents, such as immigrants residing in the country without legal permission, prisoners, and children. The plaintiffs alleged that this tabulation method dilutes the voting power of citizens residing in districts that are home to smaller concentrations of non-voting residents. The court ruled 8-0 on April 4, 2016, that a state or locality can use total population counts for redistricting purposes. The majority opinion was penned by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[35][36][37][38]

Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2016)

Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2016. At issue was the constitutionality of state legislative districts that were created by the commission in 2012. The plaintiffs, a group of Republican voters, alleged that "the commission diluted or inflated the votes of almost two million Arizona citizens when the commission intentionally and systematically overpopulated 16 Republican districts while under-populating 11 Democrat districts." This, the plaintiffs argued, constituted a partisan gerrymander. The plaintiffs claimed that the commission placed a disproportionately large number of non-minority voters in districts dominated by Republicans; meanwhile, the commission allegedly placed many minority voters in smaller districts that tended to vote Democratic. As a result, the plaintiffs argued, more voters overall were placed in districts favoring Republicans than in those favoring Democrats, thereby diluting the votes of citizens in the Republican-dominated districts. The defendants countered that the population deviations resulted from legally defensible efforts to comply with the Voting Rights Act and obtain approval from the United States Department of Justice. At the time of redistricting, certain states were required to obtain preclearance from the U.S. Department of Justice before adopting redistricting plans or making other changes to their election laws—a requirement struck down by the United States Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). On April 20, 2016, the court ruled unanimously that the plaintiffs had failed to prove that a partisan gerrymander had taken place. Instead, the court found that the commission had acted in good faith to comply with the Voting Rights Act. The court's majority opinion was penned by Justice Stephen Breyer.[39][40][41]

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015)

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 2015. At issue was the constitutionality of the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, which was established by state constitutional amendment in 2000. According to Article I, Section 4 of the United States Constitution, "the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof." The state legislature argued that the use of the word "legislature" in this context is literal; therefore, only a state legislature may draw congressional district lines. Meanwhile, the commission contended that the word "legislature" ought to be interpreted to mean "the legislative powers of the state," including voter initiatives and referenda. On June 29, 2015, the court ruled 5-4 in favor of the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, finding that "redistricting is a legislative function, to be performed in accordance with the state's prescriptions for lawmaking, which may include the referendum and the governor's veto." The majority opinion was penned by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and joined by Justices Anthony Kennedy, Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, and Samuel Alito dissented.[42][43][44][45]Race and ethnicity

- See also: Majority-minority districts

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 mandates that electoral district lines cannot be drawn in such a manner as to "improperly dilute minorities' voting power."

| “ | No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.[21] | ” |

| —Voting Rights Act of 1965[46] | ||

States and other political subdivisions may create majority-minority districts in order to comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. A majority-minority district is a district in which minority groups compose a majority of the district's total population. As of 2015, North Carolina was home to three congressional majority-minority districts.[2][3][4]

Proponents of majority-minority districts maintain that these districts are a necessary hindrance to the practice of cracking, which occurs when a constituency is divided between several districts in order to prevent it from achieving a majority in any one district. In addition, supporters argue that the drawing of majority-minority districts has resulted in an increased number of minority representatives in state legislatures and Congress.[2][3][4]

Critics, meanwhile, contend that the establishment of majority-minority districts can result in packing, which occurs when a constituency or voting group is placed within a single district, thereby minimizing its influence in other districts. Because minority groups tend to vote Democratic, critics argue that majority-minority districts ultimately present an unfair advantage to Republicans by consolidating Democratic votes into a smaller number of districts.[2][3][4]

State process

- See also: State-by-state redistricting procedures

In North Carolina, the state legislature is responsible for drawing both congressional and state legislative district lines. District maps cannot be vetoed by the governor. State legislative redistricting must take place in the first regular legislative session following the United States Census. There are no explicit deadlines in place for congressional redistricting.[47]

State law establishes the following requirements for state legislative districts:[47]

- Districts must be contiguous and compact.

- Districts "must cross county lines as little as possible." If counties are grouped together, the group should include as few counties as possible.

- Communities of interest should be taken into account.

There are no similar restrictions in place regarding congressional districts.[47]

How incarcerated persons are counted for redistricting

States differ on how they count incarcerated persons for the purposes of redistricting. In North Carolina, incarcerated persons are counted in the correctional facilities they are housed in.

District maps

Congressional districts

North Carolina comprises 14 congressional districts. The table below lists North Carolina's current U.S. Representatives.

State legislative maps

North Carolina comprises 50 state Senate districts and 120 state House districts. State senators are elected every two years in partisan elections. State representatives are elected every two years in partisan elections. To access the state legislative district maps approved during the 2020 redistricting cycle, click here.

Redistricting by cycle

Redistricting after the 2020 census

North Carolina was apportioned 14 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. This represented a net gain of one seat as compared to apportionment after the 2010 census.[48]

Enacted congressional district maps

On October 25, 2023, the North Carolina General Assembly adopted new congressional district boundaries.[5] The legislation adopting the new maps passed the State Senate by a vote of 28-18 and the State House by a vote of 64-40.[49] Both votes were strictly along party lines with all votes in favor by Republicans and all votes against by Democrats.[50][51]

The New York Times' Maggie Astor wrote, "The map creates 10 solidly Republican districts, three solidly Democratic districts and one competitive district. Currently, under the lines drawn by a court for the 2022 election, each party holds seven seats. The Democratic incumbents who have been essentially drawn off the map are Representatives Jeff Jackson in the Charlotte area, Kathy Manning in the Greensboro area and Wiley Nickel in the Raleigh area. A seat held by a fourth Democrat, Representative Don Davis, is expected to be competitive."[5]

On April 28, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court overturned their February 4, 2022, decision that the state's enacted congressional and legislative maps were unconstitutional due to partisan gerrymandering and vacated both the maps the legislature enacted in 2021 and the remedial maps used for the 2022 elections.[52] In its ruling, the court said, "we hold that partisan gerrymandering claims present a political question that is nonjusticiable under the North Carolina Constitution. Accordingly, the decision of this Court in Harper I is overruled. We affirm the three judge panel’s 11 January 2022 Judgment concluding, inter alia, that partisan gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable, political questions and dismissing all of plaintiffs’ claims with prejudice."Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many

The Court's order also said that the legislature's original 2021 maps were developed based on incorrect criteria and ruled that the General Assembly should develop new congressional and legislative boundaries to be used starting with the 2024 elections: "Just as this Court’s Harper I decision forced the General Assembly to draw the 2022 Plans under a mistaken interpretation of our constitution, the Lewis order forced the General Assembly to draw the 2021 Plans under the same mistaken interpretation of our constitution...The General Assembly shall have the opportunity to enact a new set of legislative and congressional redistricting plans, guided by federal law, the objective constraints in Article II, Sections 3 and 5, and this opinion. 'When established' in accordance with a proper understanding of the North Carolina Constitution, the new legislative plans “shall remain unaltered until the return of” the next decennial census."Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many

On February 23, 2022, the Wake County Superior Court had issued a ruling rejecting the North Carolina General Assembly's redrawn congressional map. Instead, the court enacted congressional district boundaries drawn by three court-appointed redistricting special masters. [53] The special masters were three former judges: former Superior Court Judge Tom Ross, a Democrat, former state Supreme Court Justice Bob Orr, an independent, and former state Supreme Court Justice Bob Edmunds, a Republican.[54] This map was used for North Carolina's 2022 congressional elections.

On February 4, 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled 4-3 that the enacted congressional map violated the state constitution and directed the General Assembly to develop new maps by February 18.[55] On February 15, members of the North Carolina State Senate introduced a new congressional map, which the state Senate voted 25-19 to approve and the state House voted 66-53 to approve on February 17.[56][57]

On November 4, 2021 the North Carolina General Assembly had voted to enact a new congressional map. The map passed the North Carolina State Senate 27-22 on November 2, and the North Carolina House of Representatives 65-49 on November 4.[58]

To read more about the court challenges to North Carolina's congressional maps, click here.

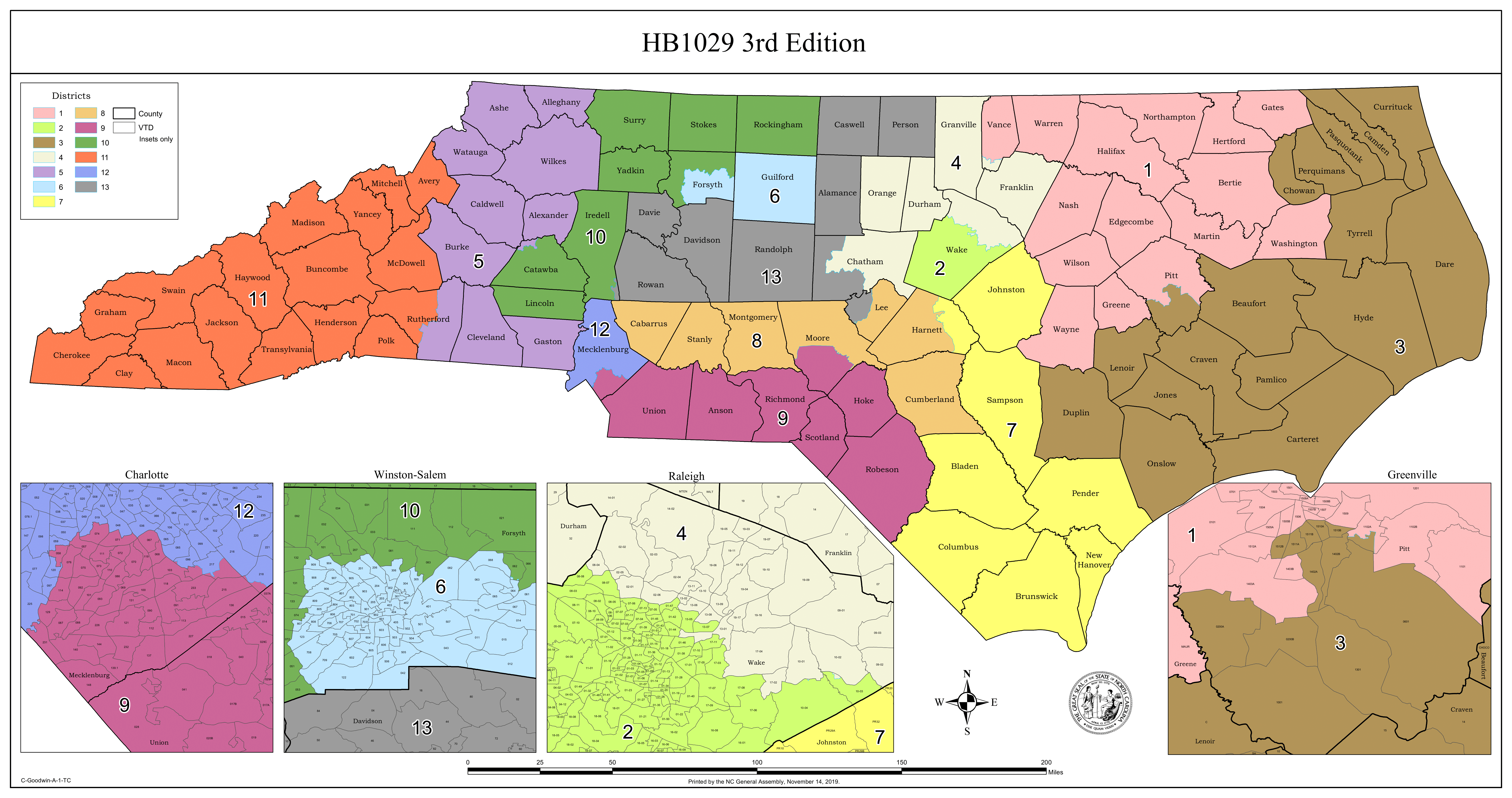

October 2023 congressional district map image

Below are the congressional maps in effect before and after the 2020 redistricting cycle.

North Carolina Congressional Districts

before 2020 redistricting cycle

Click a district to compare boundaries.

North Carolina Congressional Districts

after 2020 redistricting cycle

Click a district to compare boundaries.

Comparison of 2023 and 2022 congressional maps

Below are images displaying the congressional district boundaries that will be used for the 2024 elections as compared with those that were used in the 2022 elections.

The map below was enacted by the legislature in October 2023 and will be used for the 2024 elections.

The map below was enacted by the Wake County Superior Court in February 2022 and was used in the 2022 elections.

Reactions to district boundaries enacted in October 2023

Democratic Rep. Wiley Nickel wrote, "I don’t want to give these maps credibility by announcing a run in any of these gerrymandered districts. The maps are an extreme partisan gerrymander by Republican legislators that totally screw North Carolina voters."[59]

Senate majority leader Phil Berger said, “We wouldn’t pass these maps if we didn’t think they wouldn’t stand up in court... It wouldn’t surprise me if along the way, before we get a final decision from courts, that you might find a court that has some problem with some part of the maps — but it’s our belief that when all is said and done, these maps will stand.”[60]

Reactions to February 23, 2022, boundaries

Following the enactment of the court-drawn congressional map, North Carolina House Speaker Tim Moore (R) said: "The trial court’s decision to impose a map drawn by anyone other than the legislature is simply unconstitutional and an affront to every North Carolina voter whose representation would be determined by unelected partisan activists."[61] Eric Heberlig, a UNC-Charlotte political scientist, said "The overall representation of the state in Congress is going to align more closely to the statewide vote totals. You're going to have relatively even numbers of Democrats and Republicans representing the state in Congress rather than the lopsided Republican majority that we've seen over the last decade."[62]

2020 presidential results

The table below details the results of the 2020 presidential election in each district at the time of the 2022 election and its political predecessor district.[63] This data was compiled by Daily Kos Elections.[64]

| 2020 presidential results by Congressional district, North Carolina | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | 2022 district | Political predecessor district | ||

| Joe Biden |

Donald Trump |

Joe Biden |

Donald Trump | |

| North Carolina's 1st | 53.2% | 45.9% | 53.9% | 45.3% |

| North Carolina's 2nd | 63.6% | 34.8% | 64.3% | 34.0% |

| North Carolina's 3rd | 36.7% | 62.0% | 37.7% | 60.9% |

| North Carolina's 4th | 66.9% | 31.9% | 66.6% | 32.2% |

| North Carolina's 5th | 38.8% | 60.1% | 31.6% | 67.4% |

| North Carolina's 6th | 55.6% | 43.2% | 61.6% | 37.2% |

| North Carolina's 7th | 43.1% | 55.8% | 40.7% | 58.1% |

| North Carolina's 8th | 32.4% | 66.5% | 45.5% | 53.4% |

| North Carolina's 9th | 45.3% | 53.3% | 46.1% | 52.5% |

| North Carolina's 10th | 29.7% | 69.2% | 31.2% | 67.7% |

| North Carolina's 11th | 44.3% | 54.4% | 43.3% | 55.4% |

| North Carolina's 12th | 64.4% | 34.2% | 70.1% | 28.5% |

| North Carolina's 13th | 50.1% | 48.4% | 31.8% | 67.1% |

| North Carolina's 14th | 57.5% | 41.1% | --- | --- |

Enacted state legislative district maps

On October 25, 2023, the North Carolina General Assembly adopted new legislative district boundaries.[10] The legislation adopting the new Senate districts passed the State Senate by a vote of 28-17 and the State House by a vote of 63-40.[65] The legislation adopting the new House districts passed the State Senate by a vote of 27-17 and the State House by a vote of 62-44.[66] All four votes were strictly along party lines with all votes in favor by Republicans and all votes against by Democrats.[67][68][69][70] WUNC's Rusty Jacobs wrote that Catawba College Prof. Michael "Bitzer said Republicans have drawn maps that have a strong chance of preserving their veto-proof super majorities in both chambers of the state legislature. Bitzer noted that constitutional provisions, like requiring legislators to keep counties whole when drawing state legislative districts, make it more difficult for lawmakers to gerrymander these maps more aggressively."[71]

The Carolina Journal's Alex Baltzegar reported that "The John Locke Foundation recently released its annual Civitas Partisan Index scores for the legislative maps, which found there to be 28 Republican-leaning seats, 17 Democrat-leaning seats, and five toss-ups in the state Senate map."[10] Baltzegar also reported that "The new state House map would yield approximately 69 Republican and 48 Democratic seats, with three being in the swing category, according to Civitas’ CPI ratings. However, state House districts are smaller, and political outcomes vary to a higher degree. Many of the “lean” Republican or Democrat seats could be won by either party, and political shifts and trends will influence certain districts in the future."[10]

On April 28, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court overturned their February 4, 2022, decision that the state's enacted congressional and legislative maps were unconstitutional due to partisan gerrymandering and vacated both the maps the legislature enacted in 2021 and the remedial maps used for the 2022 elections.[72] In its ruling, the court said, "we hold that partisan gerrymandering claims present a political question that is nonjusticiable under the North Carolina Constitution. Accordingly, the decision of this Court in Harper I is overruled. We affirm the three judge panel’s 11 January 2022 Judgment concluding, inter alia, that partisan gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable, political questions and dismissing all of plaintiffs’ claims with prejudice."Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many

The Court's order also said that the legislature's original 2021 maps were developed based on incorrect criteria and ruled that the General Assembly should develop new congressional and legislative boundaries to be used starting with the 2024 elections: "Just as this Court’s Harper I decision forced the General Assembly to draw the 2022 Plans under a mistaken interpretation of our constitution, the Lewis order forced the General Assembly to draw the 2021 Plans under the same mistaken interpretation of our constitution...The General Assembly shall have the opportunity to enact a new set of legislative and congressional redistricting plans, guided by federal law, the objective constraints in Article II, Sections 3 and 5, and this opinion. 'When established' in accordance with a proper understanding of the North Carolina Constitution, the new legislative plans “shall remain unaltered until the return of” the next decennial census."Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many

On February 23, 2022, the Wake County Superior Court approved legislative maps that the General Assembly redrew after the North Carolina Supreme Court issued a 4-3 opinion on February 4, 2022, saying the state's enacted legislative maps violated the state constitution.[73] The state house map was approved by the North Carolina House of Representatives in a 115-5 vote on February 16, and by the North Carolina State Senate in a 41-3 on February 17. The state Senate map was approved by the state Senate in a 26-19 vote, and by the state House in a 67-52 vote on February 17.[74][75] These maps were used for North Carolina's 2022 legislative elections.

On November 4, the North Carolina General Assembly originally voted to enact legislative maps. The house map passed the North Carolina House of Representatives 67-49 on November 2, and the North Carolina State Senate 25-21 on November 4.[76] The senate map passed the North Carolina State Senate 26-19 on November 3 and the North Carolina House of Representatives 65-49 on Nov. 4.[77]

State Senate map

Below is the state Senate map in effect before and after the 2020 redistricting cycle.

North Carolina State Senate Districts

before 2020 redistricting cycle

Click a district to compare boundaries.

North Carolina State Senate Districts

after 2020 redistricting cycle

Click a district to compare boundaries.

State House map

Below is the state House map in effect before and after the 2020 redistricting cycle.

North Carolina State House Districts

before 2020 redistricting cycle

Click a district to compare boundaries.

North Carolina State House Districts

after 2020 redistricting cycle

Click a district to compare boundaries.

Click here to read more about the court challenges to North Carolina's congressional and legislative maps after the 2020 census.

Reactions to district boundaries enacted in October 2023

State Rep. Tim Longest (D) said, “This map secures more Republican seats than 100,000 randomly generated maps. That is unexplainable by geography, deliberately designed to maximize advantage."[78]

WUNC's Rusty Jacobs wrote that "Republican Sen. Ralph Hise, a co-chair of the Senate's redistricting committee, maintained that the maps were drawn applying traditional redistricting criteria, such as maintaining equal population across districts and minimizing the splitting of municipalities and precincts."[79]

Reactions to previous legislative maps

Regarding the first set of maps approved by the General Assembly in November, the Rep. Destin Hall (R), chair of the House Redistricting Committee, said: "This is the most transparent process in the history of this state. We voluntarily chose to be out in public and not use election data, even though by law we didn't have to do that. We chose to do that because that's the right thing to do."[80] Sen. Ralph Hise (R), co-chairman of the Senate Redistricting and Elections Committee, said: "I feel that we have complied with the law" in drawing the maps.[81] Rep. Kandie Smith (D) criticized the maps, saying: "People don't want gerrymandering. That's what we have, People don't want us packing. That's what we're doing. People don't want us to separate people with the same interest. That's what we're doing."[80] Sen. Jay Chaudhuri (D) said: "Is it going to come down to litigation being filed? Yes — and what the courts have to say about it."[81]

Following the enactment of the redrawn legislative maps, Governor Roy Cooper (D) issued a statement saying, "Today’s decision allows a blatantly unfair and unconstitutional State Senate map that may have been the worst of the bunch. Our elections should not go forward until we have fair, constitutional maps."[82] State Senator Phil Berger (R) said, "The General Assembly’s remedial legislative map met all of the court-mandated tests and were constitutionally compliant. A bipartisan panel of Special Masters affirmed that. We’re thankful for the trial court’s ruling today."[61]

Redistricting after the 2010 census

Following the 2010 United States Census, North Carolina neither gained nor lost congressional seats. In 2010, Republicans won control of both chambers of the state legislature. Consequently, Republicans dominated the 2010 redistricting process.[83]

On July 27, 2011, the General Assembly of North Carolina approved congressional and state legislative redistricting plans.[83]

On November 1, 2011, the United States Department of Justice precleared these plans. The legislature made technical corrections to the new congressional and state legislative district maps on November 7, 2011. The U.S. Department of Justice precleared the amended maps on December 8, 2011.[47]

According to The Almanac of American Politics, following the 2012 election, the first to take place under the new maps, Democrats won four of the state's 13 congressional seats, although they "won a majority of the state's votes in House races."[83]

Congressional district map challenges

Federal court challenges

Cooper v. Harris

- See also: Cooper v. Harris

On June 27, 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would hear the state's appeal of a U.S. District Court ruling that struck down two of the state's congressional district maps as racial gerrymanders. On May 22, 2017, the court upheld the lower court's determination that Districts 1 and 12 constituted an illegal racial gerrymander. Associate Justice Elena Kagan wrote the court's majority opinion, which was joined by Associate Justices Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor (Thomas also filed a separate concurring opinion).[84][85][34]

| “ | We uphold the District Court's conclusions that racial considerations predominated in designing both District 1 and District 12. For District 12, that is all we must do, because North Carolina has made no attempt to justify race-based districting there. For District 1, we further uphold the District Court's decision that [Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act] gave North Carolina no good reason to reshuffle voters because of their race. We accordingly affirm the judgment of the District Court.[21] | ” |

| —Associate Justice Elena Kagan | ||

Associate Justice Samuel Alito wrote an opinion that concurred with the majority opinion in part and dissented in part. This opinion was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy.[34]

| “ | Reviewing the evidence outlined above, two themes emerge. First, District 12's borders and racial composition are readily explained by political considerations and the effects of the legislature's political strategy on the demographics of District 12. Second, the majority largely ignores this explanation, as did the court below, and instead adopts the most damning interpretation of all available evidence.[21] | ” |

| —Associate Justice Samuel Alito | ||

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch did not participate in the case.[34]

For full details on this case, see this article.

Common Cause v. Rucho

- See also: Common Cause v. Rucho and Rucho v. Common Cause

On August 27, 2018, a three-judge panel of the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina ruled that North Carolina's congressional district map constituted an illegal partisan gerrymander. The court ruled 2-1 on the matter, with Judges James Wynn and Earl Britt forming the majority. Wynn wrote the majority opinion. Judge William Osteen wrote an opinion that concurred in part and dissented in part.[86]

The court ruled that no elections occurring after November 6, 2018, could be conducted using the congressional map it struck down. The court did not, however, order an immediate remedy. Instead, it asked the parties to the suit to submit briefs by August 31, 2018, "addressing whether this Court should allow the State to conduct any future elections using the 2016 Plan."[86]

On September 4, 2018, the district court announced it would not order changes to the map before November’s election, finding that “imposing a new schedule for North Carolina's congressional elections would, at this late juncture, unduly interfere with the State's electoral machinery and likely confuse voters and depress turnout.” On October 1, 2018, the defendants appealed the district court's decision to the United States Supreme Court, which agreed to take up the case and scheduled oral argument for March 26, 2019. On June 27, 2019, the high court issued a joint ruling in this case and Lamone v. Benisek, finding that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions that fall beyond the jurisdiction of the federal judiciary. The high court ruled 5-4, with Chief Justice John Roberts penning the majority opinion, joined by Associate Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh. Associate Justice Elena Kagan penned a dissent, joined by Associate Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor. The high court remanded the case to the lower court with instructions to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. See Rucho v. Common Cause for more information.[87][88]

State court challenges

On September 27, 2019, opponents of the state's congressional district plan filed suit in state superior court, alleging that the district plan enacted by the state legislature in 2016 constituted a partisan gerrymander in violation of state law. The plaintiffs asked that the court bar the state from using the maps in the 2020 election cycle. On October 28, 2019, a three-judge panel of the state superior court granted this request, enjoining further application of the 2016 maps. In its order, the court wrote, "The loss to Plaintiffs' fundamental rights guaranteed by the North Carolina Constitution will undoubtedly be irreparable if congressional elections are allowed to proceed under the 2016 congressional districts." The court did not issue a full decision on the merits, stating that "disruptions to the election process need not occur, nor may an expedited schedule for summary judgment or trial even be needed, should the General Assembly, on its own initiative, act immediately and with all due haste to enact new congressional districts." The same three-judge panel, comprising Judges Paul C. Ridgeway, Joseph N. Crosswhite, and Alma L. Hinton, struck down the state's legislative district plan on similar grounds on September 3, 2019.[89]

On November 14, 2019, the state House approved a remedial district plan (HB1029) by a vote of 55-46 .The vote split along party lines, with all Republicans voting in favor of the bill and all Democrats voting against it. The state Senate approved the bill on November 15, 2019, by a vote of 24-17. This vote also split along party lines. An image of the remedial map can be accessed here.[90][91]

Democrats opposed the remedial plan and announced their intention to challenge it in court. Eric Holder, former U.S. Attorney General and chair of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, said, "The congressional map passed by Republicans in the North Carolina legislature simply replaces one partisan gerrymander with a new one. This new map fails to respond to the court’s order by continuing to split communities of interest, packing voters in urban areas, and manipulating the district lines to provide Republicans with an unfair partisan advantage." Meanwhile, Republican Representative Patrick McHenry dismissed these criticisms: "Eric Holder and (former President) Barack Obama have raised a lot of money for this outcome, and they’ve pursued a really aggressive legal strategy for their partisan outcomes, and right now they’re calling it partisan gerrymandering, but what they’re seeking is partisan gerrymandering for the left. We basically have a Wild West of redistricting. This will be the fourth map in six cycles, and I think that is so confusing for voters and has a major negative impact on voters."[92]

On November 20, 2019, the court issued an order delaying the congressional candidate filing period for the 2020 election cycle pending resolution of the case. The filing period had originally been set to open on December 2, 2019, and close on December 20, 2019. The court scheduled a hearing for December 2, 2019, to consider both the plaintiffs' and the defendants' motions for summary judgment. On December 2, 2019, the court ruled unanimously that elections in 2020 would take place under the remedial maps. The court did not issue a final decision on the merits, saying it would need more time to evaluate the maps and the relevant factual and constitutional issues. The court ordered that candidate filing open immediately. The plaintiffs announced that they would not appeal the decision. Holder said, "After nearly a decade of voting in some of the most gerrymandered districts in the country, courts have put new maps in place that are an improvement over the status quo, but the people still deserve better."[93][94]

State legislative district map challenges

Federal court challenges

On June 5, 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a unanimous per curiam ruling affirming a U.S. District Court decision that 28 state legislative district maps had been subject to an illegal racial gerrymander. However, the district court was directed to reconsider its order for special elections in 2017, with the high court finding that the district court had not conducted the proper analysis in determining its remedy.[95]

On July 31, 2017, the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina issued an order denying plaintiff's request for a special election using a new district map in 2017.[96] The court ordered state lawmakers to enact a new district map by September 1, 2017, for use in the 2018 general election.[96]

On August 30, 2017, the remedial House and Senate district plans (HB 927 and SB 691, respectively) became law.[97][98][99][100]

On October 26, 2017, the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina issued an order appointing Nate Persily as a special master "to assist the Court in further evaluating and, if necessary, redrawing" the revised maps.[101]

On December 1, 2017, Persily made his final recommendations. The district court panel overseeing the case adopted Persily's recommendations on January 19, 2018. On January 21, 2018, state Republican lawmakers filed a motion requesting that the court stay its order pending an appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States.[102][103]

On February 6, 2018, the Supreme Court issued a partial stay of the district court's order. The stay applied to five revised state House districts in Wake and Mecklenburg counties (four in Wake County, one in Mecklenburg). The four remaining district maps adopted by the district court (in Hoke, Cumberland, Guilford, Sampson, and Wayne counties) were permitted to stand.[104][105][106]

On June 28, 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a per curiam ruling in North Carolina v. Covington, affirming in part and remanding in part the district court decision (i.e., allowing the court's order to stand as it applied to districts in Hoke, Cumberland, Guilford, Sampson, and Wayne counties but overturning the district court's decision as it applied to districts in Wake and Mecklenburg counties).[107][108][109][110]

For full details on this process, click "[Show more]" below.

On August 11, 2016, the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina ruled that North Carolina's state legislative district map constituted an illegal racial gerrymander. The court found that the General Assembly of North Carolina had placed too many minority voters into a small number of districts, thereby diluting the impact of their votes. The court determined that nine state Senate districts and 19 state House districts had been subject to an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. The court ruled that the existing map could be used for the 2016 general election. However, the court ordered state lawmakers to draft a new map during their next legislative session.[111][112]

On November 29, 2016, the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina ordered the state to conduct special elections for the state legislature in 2017 using new state legislative district maps. The court ordered state lawmakers to redraw state legislative district maps by March 15, 2017. In its ruling, the court wrote the following:[113][114]

| “ | While special elections have costs, those costs pale in comparison to the injury caused by allowing citizens to continue to be represented by legislators elected pursuant to a racial gerrymander. The court recognizes that special elections typically do not have the same level of voter turnout as regularly scheduled elections, but it appears that a special election here could be held at the same time as many municipal elections, which should increase turnout and reduce costs.[21] | ” |

| —United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina | ||

State Representative David Lewis (R) and State Senator Bob Rucho (R) issued a press release on November 29, 2016, criticizing the order:>

| “ | This politically motivated decision, which would effectively undo the will of millions of North Carolinians just days after they cast their ballots, is a gross overreach that blatantly disregards the constitutional guarantee for voters to duly elect their legislators to biennial terms.[21] | ” |

| —Representative David Lewis (R) and Senator Bob Rucho (R) | ||

The North Carolina Democratic Party (NCDP) voiced its support of the special elections following the federal order:[115]

| “ | The North Carolina Democratic Party applauds the federal court's order to redraw these gerrymandered legislative districts. Our elected officials should fairly represent our state, and redrawn districts will help level the playing field.[21] | ” |

| —NCDP Executive Director Kimberly Reynolds | ||

On December 30, 2016, Republican legislators petitioned the United States Supreme Court to intervene and stay (i.e., suspend) the district court's decision. On January 10, 2017, the high court issued an order halting the special elections pending appeals.[116][117][118]

North Carolina State Senate President Pro tem Phil Berger (R) and North Carolina House Speaker Timothy K. Moore (R) said in a joint statement on the U.S. Supreme Court temporarily blocking the order that:[119]

| “ | [We] … are grateful the U.S. Supreme Court has quashed judicial activism and rejected an attempt to nullify the votes of North Carolinians in the 2016 legislative elections.[21] | ” |

| —Representative Tim Moore (R) and Senator Phil Berger (R) | ||

Senate Minority Leader Dan Blue (D) said in a town hall in March 2017 that he was confident the special elections would happen in 2017. He said the following:[119]

| “ | I’m confident, and most of the lawyers who practice in this area [of law] …are confident that the [U.S.] Supreme Court, when they look at the case, because it has been appealed up there, will uphold the findings of the federal court that this is unconstitutional. The case law says they have no choice.[21] | ” |

| —Senator Dan Blue (D) | ||

On June 5, 2017, the Supreme Court of the United States issued a unanimous per curiam ruling affirming the decision of the district court, which had earlier determined that the aforementioned 28 districts had been subject to an illegal racial gerrymander. However, the district court was directed to reconsider its order for special elections in 2017, with the high court finding that the district court had not undertaken the proper analysis in determining its remedy:[120]

| “ | Relief in redistricting cases is "fashioned in the light of well-known principles of equity." A district court therefore must undertaken an 'equitable weighing process' to select a fitting remedy for the legal violations it has identified, taking account of "what is necessary, what is fair, and what is workable." ... Rather than undertaking such an analysis in this case, the District Court addressed the balance of equities in only the most cursory fashion. ... For that reason, we cannot have confidence that the court adequately grappled with the interests on both sides of the remedial question before us.[21] | ” |

| —Supreme Court of the United States | ||

On July 31, 2017, the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina issued an order denying the plaintiff's request for a special election using a new district map in 2017.[96]

| “ | We do not disagree with Legislative Defendants that there are many benefits to a time line that allows for the General Assembly (1) to receive public feedback on the criteria to be used in drawing the remedial districts and proposed remedial districting plans applying those criteria; (2) to revise the proposed plans based on that feedback; and (3) to engage in robust deliberation. Although we appreciate that Legislative Defendants could have been gathering this information over the past months and weeks, Plaintiffs’ two-week schedule does not provide the General Assembly with adequate time to meet their commendable goal of obtaining and considering public input and engaging in robust debate and discussion. Therefore, we prefer to give the legislature some additional time to engage in a process substantively identical to the one they have proposed.[21] | ” |

| —United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina | ||

The court ordered state lawmakers to enact a new district map by September 1, 2017, for use in the 2018 general election. State lawmakers had proposed a November 15, 2017, deadline; the court ruled that this "deadline would interfere with the ability of potential candidates to prepare for the upcoming 2018 election."[96]

On August 10, 2017, the House and Senate redistricting committees adopted criteria for the new state legislative district map. These criteria included the following:[121][122][123]

- Districts must have approximately equal populations.

- Districts must be contiguous (i.e., all parts of a district must be connected).

- Districts must adhere to county groupings.

- Districts must be compact.

- Lawmakers should minimize the splitting of precincts when drawing districts.

- Lawmakers should take into account existing municipal boundaries when drawing districts.

- Lawmakers can take into account political considerations and election data when drawing districts.

- Lawmakers can make efforts to avoid pairing incumbents within the same district.

- Lawmakers cannot take race into consideration when drawing districts.

State Democrats criticized some of these criteria. Representative Henry Michaux, Jr. (D), referring to the rule that prevents lawmakers from considering race, said, "How are you going to prove to the court that you did not violate their order in terms of racial gerrymandering? You cannot escape the fact that race has to be in there somewhere." David Lewis (R), chair of the House redistricting committee, said, "We do not believe it is appropriate given the court's order in this case for these committees to consider race when drawing districts." House Minority Leader Darren Jackson (D), referring to the criterion that permits lawmakers to consider incumbency, said "It just seems ridiculous to me that you get to say, 'We will protect the incumbents elected using unconstitutional maps." Lewis said, "Every result from where a line is drawn will be an inherently political thing. It is right and relevant to review past performance in drawing districts." Drafts of the new district maps were slated to be released in advance of expected public hearings on August 22 or 23.[121][122][124]

On August 19 and 20, 2017, the General Assembly of North Carolina released drafts of revised district maps for the state House and Senate, respectively. Public hearings on the maps took place on August 23, 2017, in seven different parts of the states: Raleigh, Charlotte, Fayetteville, Hudson, Jamestown, Weldon, and Washington.[125][126][127][128]

On August 28, 2017, the House passed HB 927, the House redistricting plan, and sent it to the Senate. HB 927 cleared the Senate on August 30, 2017, and became law. As enacted, the state House district map paired incumbents in three districts (i.e., incumbents who, under the prior plan, resided in separate districts):[129]

- Representatives Jean Farmer-Butterfield (D) and Susan Martin (R) in District 24.

- Representatives Jon Hardister and John Faircloth, both Republicans, in District 61.

- Representatives Carl Ford and Larry Pittman, both Republicans, in District 83.

The House map enacted by the legislature on August 30, 2017, is displayed below. For further details, please click here.

On August 28, 2017, the Senate passed SB 691, the Senate redistricting plan, and sent it to the House. SB 691 cleared the House on August 30, 2017, and was enacted into law. As enacted, the state Senate district map paired incumbents in four districts (i.e., incumbents who, under the prior plan, resided in separate districts):[130][131][132][133]

- Senators Erica Smith-Ingram (D) and Bill Cook (R) in District 3; on August 29, Cook announced that he would not seek re-election in 2018.

- Senators Chad Barefoot and John Alexander, both Republicans, in District 18; on August 20, Barefoot announced that he would not seek re-election in 2018.

- Senators Joyce Krawiec and Dan Barrett, both Republicans, in District 31.

- Senators Deanna Ballard and Shirley Randleman, both Republicans, in District 45.

The Senate map enacted by the legislature on August 30, 2017, is displayed below. For further details, please click here.

On October 26, 2017, the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina issued an order appointing Nate Persily as a special master "to assist the Court in further evaluating and, if necessary, redrawing" the revised maps. The court indicated that the redrawn maps for Senate Districts 21 and 28 and House Districts 21, 36, 37, 40, 41, 57, and 105 "either fail to remedy the identified constitutional violation or are otherwise legally unacceptable." The court did not provide a precise deadline in its order; it did, however, indicate that the "upcoming filing period for the 2018 election cycle" factored into its decision to appoint a special master.[134] North Carolina Democratic Party chairman Wayne Goodwin issued a statement via Twitter in support of the ruling: "This is a stunning rebuke of Republican legislators who refused to fix their racist maps and a collosal political failure from Speaker Moore and Senator Berger. They had a chance to fix their maps and doubled down instead — and now the courts will fix it for them." On October 30, 2017, Republican lawmakers filed a motion objecting to the appointment of Persily as special master; they argued that there was ample time for the state legislature to make any court-ordered amendments to the maps before the 2018 candidate filing period. GOP lawmakers also argued that Persily might be biased because he "has a history of commenting negatively on North Carolina districting matters and working on districting matters with organizations who are allied with the plaintiffs in this case."[135][136]

On November 13, 2017, Persily issued draft redistricting plans. In the order announcing the release of the draft plans, Persily noted that "these draft plans are provided at this early date to give the parties time to lodge objections and to make suggestions, as to unpairing incumbents or otherwise, that might be accommodated in the final plan," which was due to the court by December 1, 2017. Persily's proposed maps can be accessed here.[137]

On December 1, 2017, Persily issued his final recommendations, which he said "represent a limited response to a select number of districts that require alteration to comply with the law." Rep. David Lewis (R) and Sen. Ralph Hise (R), the chairmen of their chambers' respective redistricting committees, issued a statement criticizing Persily's recommendations: "By making many changes Democrats demanded, Mr. Persily has confirmed our worst suspicions: this entire ‘judicial process’ is little more than a thinly-veiled political operation where unelected judges, legislating from the bench, strip North Carolinians of their constitutional right to self-governance by appointing a left-wing California professor to draw districts handing Democrats control of legislative seats they couldn’t win at the ballot box." Wayne Goodwin, North Carolina Democratic Party (NCDP) chairman, defended Persily's recommendations: "The independent, non-partisan special master had one task – to fix Republicans’ unconstitutional racial gerrymander after Speaker Moore and Leader Berger refused. NCDP applauds the special master for doing just that, and for giving voters in the affected districts a chance to pick their representatives again instead of the other way around. Republicans made this bed and now they must lie in it, and their efforts to delegitimize the special master and our judicial system are dangerous and destructive." The district court panel overseeing the case issued an order adopting Persily's recommendations on January 19, 2018. On January 21, 2018, state Republican lawmakers filed a motion requesting that the court stay its order pending an appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States. On February 6, 2018, the Supreme Court issued a partial stay against the district court's order. The stay applied to five revised state House districts in Wake and Mecklenburg counties (four in Wake County, one in Mecklenburg). The four remaining district maps adopted by the district court (in Hoke, Cumberland, Guilford, Sampson, and Wayne counties) were permitted to stand. On June 28, 2018, the Supreme Court of the United States issued a per curiam ruling in North Carolina v. Covington, affirming in part and remanding in part the district court decision (i.e., allowing the court's order to stand as it applied to districts in Hoke, Cumberland, Guilford, Sampson, and Wayne counties but overturning the district court's decision as it applied to districts in Wake and Mecklenburg counties):[138][139][140][141][142][143][144][145][146]

| “ | The only injuries [the maps' challengers'] established in this case were that they had been placed in their legislative districts on the basis of race. The District Court's remedial authority was accordingly limited to ensuring that the plaintiffs were relieved of the burden of voting in racially gerrymandering legislative districts. But the District Court's revision of the House districts in Wake and Mecklenburg Counties had nothing to do with that. Instead, the District Court redrew those districts because it found that the legislature's revision of them violated the North Carolina Constitution's ban on mid-decade redistricting, not federal law. ... The District Court's decision to override the legislature's remedial map on that basis was clear error. ... Once the District Court had ensured that the racial gerrymanders at issue in this case were remedied, its proper role in North Carolina's legislative redistricting process was at an end.[21] | ” |

| —Supreme Court of the United States (per curiam opinion) | ||

State court challenges

On February 7, 2018, opponents of the 2017 maps adopted by the state legislature petitioned a state court to intervene and order that the Persily maps be implemented in Wake and Mecklenburg counties. On February 12, 2018, a panel of state superior court judges declined this request. On February 21, 2018, opponents filed another suit in state court challenging the legality of the remedial Wake County district maps (House Districts 36, 37, 40, and 41). The plaintiffs requested that the court intervene to prevent the map's use in future elections. On April 13, 2018, a panel of state superior court judges denied the plaintiffs' request for a stay against the challenged maps. The panel, comprising Judges Paul C. Ridgeway, Joseph N. Crosswhite, and Alma L. Hinton, while noting that the plaintiffs had "demonstrated a reasonable likelihood of success on the merits of their claims," said issuing a stay at this juncture "would interrupt voting by citizens already underway."[147][148][149][150]

On February 1, 2019, the court issued an order setting a July 15, 2019, start date for a trial on the merits of the claims lodged by the maps' opponents. The trial concluded on July 26, 2019.[151][152]

On September 3, the court issued its ruling, striking down the state's legislative district plan as an impermissible partisan gerrymander under the state constitution. In their ruling, Judges Ridgeway, Crosswhite, and Hinton wrote, "[The] 2017 Enacted Maps, as drawn, do not permit voters to freely choose their representative, but rather representatives are choosing voters based upon sophisticated partisan sorting. It is not the free will of the people that is fairly ascertained through extreme partisan gerrymandering. Rather, it is the carefully crafted will of the map drawer that predominates."[153]

Bob Phillips, executive director of Common Cause North Carolina, praised the court's decision: "The court has made clear that partisan gerrymandering violates our state's constitution and is unacceptable. Thanks to the court's landmark decision, politicians in Raleigh will no longer be able to rig our elections through partisan gerrymandering." Senate Majority Leader Phil Berger (R), although critical of the court's ruling, announced that state Republicans would not appeal the decision: "We disagree with the court's ruling as it contradicts the Constitution and binding legal precedent, but we intend to respect the court's decision and finally put this divisive battle behind us."[154]

The court ordered state lawmakers to draft remedial maps by September 18, 2019, for use in the 2020 election cycle. On September 17, 2019, the state legislature approved H1020 and SB 692, remedial district plans for the state House and Senate, respectively. On October 28, 2019, the court approved the remedial plans. The remedial House plan can be accessed here. The remedial Senate plan can be accessed here.[153][155]

On November 1, 2019, the plaintiffs petitioned the state supreme court to review eight remedial state House districts in the Forsyth-Yadkin and Columbus-Pender-Robeson county groupings, alleging that these districts remained impermissible partisan gerrymanders.[156]

State legislation and ballot measures

Redistricting legislation

The following is a list of recent redistricting bills that have been introduced in or passed by the North Carolina state legislature. To learn more about each of these bills, click the bill title. This information is provided by BillTrack50.

Note: Due to the nature of the sorting process used to generate this list, some results may not be relevant to the topic. If no bills are displayed below, no legislation pertaining to this topic has been introduced in the legislature recently.

Redistricting ballot measures

Ballotpedia has tracked the following ballot measure(s) relating to redistricting in North Carolina.

- North Carolina Senatorial Districts, Amendment 3 (1954)

- North Carolina Legislative Reapportionment, Amendment 2 (1962)

- North Carolina Legislative Membership, Amendment 1 (January 1964)

Political impacts of redistricting

Competitiveness

There are conflicting opinions regarding the correlation between partisan gerrymandering and electoral competitiveness. In 2012, Jennifer Clark, a political science professor at the University of Houston, said, "The redistricting process has important consequences for voters. In some states, incumbent legislators work together to protect their own seats, which produces less competition in the political system. Voters may feel as though they do not have a meaningful alternative to the incumbent legislator. Legislators who lack competition in their districts have less incentive to adhere to their constituents’ opinions."[157]

In 2006, Emory University professor Alan Abramowitz and Ph.D. students Brad Alexander and Matthew Gunning wrote, "[Some] studies have concluded that redistricting has a neutral or positive effect on competition. ... [It] is often the case that partisan redistricting has the effect of reducing the safety of incumbents, thereby making elections more competitive."[158]

In 2011, James Cottrill, a professor of political science at Santa Clara University, published a study of the effect of non-legislative approaches (e.g., independent commissions, politician commissions) to redistricting on the competitiveness of congressional elections. Cottrill found that "particular types of [non-legislative approaches] encourage the appearance in congressional elections of experienced and well-financed challengers." Cottrill cautioned, however, that non-legislative approaches "contribute neither to decreased vote percentages when incumbents win elections nor to a greater probability of their defeat."[159]

In 2021, John Johnson, Research Fellow in the Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education at Marquette University, reviewed the relationship between partisan gerrymandering and political geography in Wisconsin, a state where Republicans have controlled both chambers of the state legislature since 2010 while voting for the Democratic nominee in every presidential election but one since 1988. After analyzing state election results since 2000, Johnson wrote, "In 2000, 42% of Democrats and 36% of Republicans lived in a neighborhood that the other party won. Twenty years later, 43% of Democrats lived in a place Trump won, but just 28% of Republicans lived in a Biden-voting neighborhood. Today, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to live in both places where they are the overwhelming majority and places where they form a noncompetitive minority."[160]

State legislatures after the 2010 redistricting cycle

In 2014, Ballotpedia conducted a study of competitive districts in 44 state legislative chambers between 2010, the last year in which district maps drawn after the 2000 census applied, and 2012, the first year in which district maps drawn after the 2010 census applied. Ballotpedia found that there were 61 fewer competitive general election contests in 2012 than in 2010. Of the 44 chambers studied, 25 experienced a net loss in the number of competitive elections. A total of 17 experienced a net increase. In total, 16.2 percent of the 3,842 legislative contests studied saw competitive general elections in 2010. In 2012, 14.6 percent of the contests studied saw competitive general elections. An election was considered competitive if it was won by a margin of victory of 5 percent or less. An election was considered mildly competitive if it was won by a margin of victory between 5 and 10 percent. For more information regarding this report, including methodology, see this article.

There were two competitive races for the North Carolina State Senate in 2012, compared to five in 2010. There were four mildly competitive state Senate elections in 2012, compared to six in 2010. This amounted to a net loss of two competitive elections.

There were nine competitive races for the North Carolina House of Representatives in 2012, compared to 10 in 2010. There were six mildly competitive state House elections in 2012, compared to 11 in 2010. This amounted to a net loss of six competitive elections.

Recent news

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms Redistricting North Carolina. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also

- United States census, 2020

- Redistricting in North Carolina after the 2010 census

- Redistricting

- State-by-state redistricting procedures

- Majority-minority districts

- State legislative and congressional redistricting after the 2010 census

- Margin of victory in state legislative elections before and after the 2010 census

- Margin of victory analysis for the 2014 congressional elections

External links

- All About Redistricting

- Dave's Redistricting

- FiveThirtyEight, "What Redistricting Looks Like In Every State"

- National Conference of State Legislatures, "Redistricting Process"

- FairVote, "Redistricting"

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 All About Redistricting, "Why does it matter?" accessed April 8, 2015

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 newsked-initial-redistricting-maps-met-with-skepticism-and-dismay/Content?oid=2583046 Indy Week, "Cracked, stacked and packed: Initial redistricting maps met with skepticism and dismay," June 29, 2011 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "indy" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "indy" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "indy" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 The Atlantic, "How the Voting Rights Act Hurts Democrats and Minorities," June 17, 2013

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Redrawing the Lines, "The Role of Section 2 - Majority Minority Districts," accessed April 6, 2015

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 The New York Times, "North Carolina Republicans Approve House Map That Flips at Least Three Seats," October 26, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "Senate Bill 757 / SL 2023-145," accessed October 26, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "House Roll Call Vote Transcript for Roll Call #613," accessed October 26, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "Senate Roll Call Vote Transcript for Roll Call #492," accessed October 26, 2023

- ↑ The New York Times, "North Carolina Court, With New Partisan Mix, Reverses Itself on a Key Voting Case," April 28, 2023

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 The Carolina Journal, "New state House, Senate, and congressional maps finalized," October 25, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "Senate Bill 758 / SL 2023-146," accessed October 26, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "House Bill 898 / SL 2023-149," accessed October 26, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "House Roll Call Vote Transcript for Roll Call #614," accessed October 26, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "Senate Roll Call Vote Transcript for Roll Call #499," accessed October 26, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "Senate Roll Call Vote Transcript for Roll Call #504," accessed October 26, 2023

- ↑ North Caroliina General Assembly, "House Roll Call Vote Transcript for Roll Call #604," accessed October 26, 2023